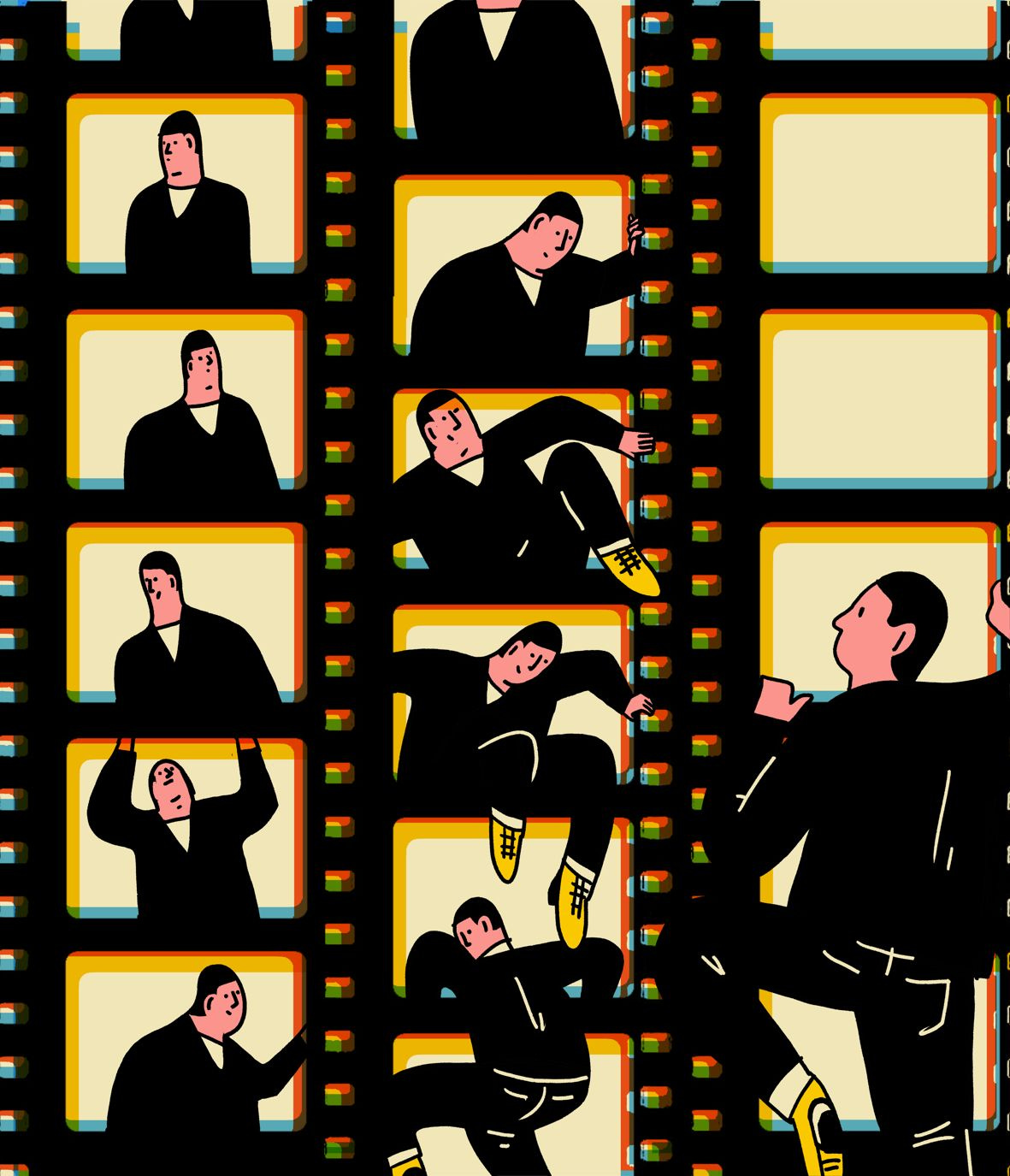

Are you stuck in movie logic?

Consider just saying what the problem is

Have you ever noticed just how much of the drama in movies is generated by an unspoken rule that the characters aren’t allowed to communicate well? Instead of naming the problem, they’re forced to skirt around it until the plot makes it impossible to ignore. It’s the cheapest way to build effective drama, but if you don’t fully dissolve yourself in the movie logic, the whole time you want to scream, “can’t anyone just talk about what’s happening directly?!”

Take La La Land. A huge part of the drama of the movie could have been avoided if the Ryan Gosling character said to the Emma Stone character: “I feel pressure to get a steady gig that includes lots of time on the road because I sense you want me to grow up and get real about my career. Could we talk about whether that’s what you actually want, and get clearer about our priorities?” Instead, they never talk about it, and the relationship explodes as a result of their misaligned expectations.

Or: Good Will Hunting. The entire movie feels like it could’ve been skipped if literally any emotionally intelligent person said to Matt Damon’s character: “I feel like you have a tremendous amount of intellectual potential that you’re wasting here — why are you getting in fights rather than trying to do something interesting?”

Communication failures like these make for good storytelling where we, the audience, get to watch the characters stumble towards understanding. But you shouldn’t live like someone waiting for the screenwriter of your life to arrange a convenient resolution. Functional people don’t let things linger unspoken — they name what’s facing them out loud.

It sounds like such a simple thing. And yet, so many of us don’t do it. It’s my experience that movie logic is endemic in dysfunctional organizations, friendships, and marriages. People walk around in a haze of denial, simply assuming that their concerns will disappear. They wait until the problem can’t possibly be ignored anymore, instead of naming it well before it becomes critical. Maybe they don’t even realize at a conscious level that the dynamic in question is capable of being named; they just take it as a background fact about the universe that they can strain against but not change.

What does it look like when you break out of movie logic? I remember the first time I realized I could do this. I was at a bar during my first year of law school with a bunch of people from my class, including a woman with whom I had an awkward dynamic stemming from an unfortunate misunderstanding about a guy. This awkwardness had calcified in my emotional brain to “we don’t like each other, we have beef.” But on that particular evening I had a moment of clarity, and instead of trying to avoid her I walked up to her and said, “I feel like we got off on the wrong foot because of that stupid thing, and I’m sorry about that — I don’t have anything against you at all.” In an instant, the look of flat wariness she’d put on when she saw me walking over melted into relief, and she said “I’m so glad you said that, I’ve been feeling awful about it.” She went on to be my closest friend in law school.

Outcomes like this are common when you figure out how to break the fourth wall. Whether or not both of you were already conscious of the real, underlying issue, when it is spoken out loud, the result is usually relief, like a spell has been broken. Even if the content is uncomfortable, it feels good in the way cutting through layers of unreality always does.

Some other lines of dialogue that would make for bad movies, but good living:

“I’ve noticed that lately, every time we have plans to hang out one-on-one, you invite someone else to join us — is that intentional?”

“I always feel a little awkward around you, and I’m worried it comes across as me not liking you — I just wanted to say that’s not the case.”

“I’ve been feeling a low-level tension between us, like maybe we’re quietly annoyed at each other but trying to stay polite. Is that just me?”

“It sometimes seems like when I push back in meetings, it changes the energy in the room — like maybe you’re afraid to engage with me as directly as you do other people. Does that feel true?”

Reading these examples, you might have noticed that it’s rare to hear people talk like this. I think there are a couple of reasons for that.

One is that it’s easy to mistake silence for informed diplomacy. If your manager is stressing you out, and you are putting up with it, it’s easy to think that you’re just being a good employee, and everyone is aware of how good you’re being. But unless your manager is quite emotionally intelligent, they may have no idea that you’re unhappy, especially if you’re engaging in people-pleasing behavior to try and cover it up.

Another reason is that it can feel like by naming an issue, you are making it into a big deal. But problems are real, and exert a toll on you, whether you name them or not. Naming the issue means you can interact with it.

Finally — often, the people who are most eager to name issues kind of suck. They are critical, judgmental people who lob opinions about how others should live without skill. Think of the person you’ve just met who confidently offers unsolicited advice about whatever they imagine your problem is.

But the answer to this is not to maintain the conspiracy of silence. The answer is to get skillful at naming issues.

Tip 1: Take yourself outside the movie

Before you even name an issue, it can help to ask: Actually, is this really the important issue to name? Or is my feeling about the issue a manifestation of something deeper that would be even more powerful to tackle?

For example, let’s say you want to tell a friend that you were bothered by the way they were bragging about how lavish and expensive their wedding was. Is that really the root issue? Or is the real issue an underlying dynamic of competitiveness stoked by both parties, where the relationship is worse off because both of you fill every conversation with social status claims?

To locate the possibility of going deeper, it can be helpful to take the movie metaphor literally — if you were an audience member watching the movie, what would you be screaming at yourself to say? What would a reader of this screenplay say the real, big unnamed issue is?

Tip 2: If you feel you can’t name the problem, say that

Let’s say you want to name a problem in one of your relationships, but you’re worried that presenting the problem would start an argument. Congratulations. You have now found the problem to name. You are allowed to say the following: “There’s an issue I see in our relationship, and I want to address it so our relationship is stronger. But I’m nervous about naming it, because I’m worried that it could start an argument, and I really don’t want you to feel attacked.”

This is advice that is applicable annoyingly often, to any meta-problem that makes a conversation difficult. You can always address the secondary problem. Many relationship advice conversations I have with friends go like this.

Friend: “I want to talk about [issue] with my partner, but when I get into the issue, I get flustered about it and stop making sense.”

Me: “Okay, what if you say that: I want to talk about this issue but it makes me flustered, and I stop making sense.”

Friend: “... Oh, why didn’t I think of that?”

The reason that they don’t think of it, I suspect, is that one way to avoid difficult conversations is to come up with a secondary problem that offers an excuse for avoiding the conflict, and then assume it’s impassable.

Tip 3: Name things before you’re sure of what they are

Sometimes, it’s hard to name a problem because you don’t fully understand it yet. But that’s completely okay — in many settings, you don’t even have to fully understand your feelings, or what is wrong, before you name a conflict. It can be powerful to say: “Something felt off about that meeting, like maybe something important wasn’t being said.” Or: “I think there’s something weird happening in this conversation, but I don’t know what it is.”

Human beings are near-telepathic in our ability to sense when an interpersonal dynamic is off — when someone is emotionally uncomfortable, or engaging in concealment. We all know the itchy feeling when nobody in an interaction is really being sincere. Pretty amazing how psychic we are, right?

Yes, we are psychic, but we are also stupid. Our sense that something is weird is often accurate, but our stories about precisely what the weirdness represents are often way, way off. So, in order to move from an interesting intuition to an accurate story about reality, it helps to enlist other people in the discussion by naming the intuition.

I’ve historically been hesitant to present my intuitions, because it feels sloppy. But having on more than one occasion overcome a “funny feeling” about a good-on-paper candidate to bad results, I’m now eager to make statements like: “It might not mean anything, but I can’t shake a weird feeling about that person. Do you get that same thing?”

This requires a little social discernment, of course. If you are a junior employee in a new workplace, it might not be tactically prudent to approach the CEO with the statement, “hey, couldn’t help but notice that the vibes are off.” But if you work closely with someone, err on the side of transparency.

You might ask — ultimately, what is so wrong with movie logic? Maybe you don’t have to address everything now. Sometimes a solution will present itself. And, I agree. It’s not fatal to, on occasion, engage in a little bit of hopeful silence, to see whether the problem you’re having with someone else is just a mood that might shift.

But over time, hopeful silence has corrosive effects. If you don’t name the real problems in your life, you eventually become alienated from your inner compass. You stop paying attention to your life on an experiential level, because you want to live in a pretend world of self-consolation. You lose the ability to see your life honestly.

Sometimes, I notice this when working with people who have spent time in organizations with poor feedback cultures. They have been taught that it’s so bad to name problems that they focus on resolving acute issues while keeping the peace, all the while navigating an invisible psychological obstacle course. Over time, they become trapped in people-pleasing, and this can blind them to real issues in the substance of their work. When people are like this, it’s difficult to get them to improve, because they see it as psychologically damaging to recognize their own limitations.

This is a skill I’m still working to get better at. It’s truly rare that someone reaches the ceiling — having no resistance to naming issues, and being maximally skillful about doing it. I’m not there yet. But I’m on my way, and it feels good to be moving in that direction. The better I get at it, the less I’m threatened by conflict, and the more it seems like an opportunity to clarify what’s really going on, to grow closer to myself and others. I don’t want to be the character in the movie who’s hopelessly buffeted by intrigue and too scared to investigate it dispassionately. I want to be like the director, who thoroughly understands the drama of each character, and finds the scene all the more interesting as a result.

Sign up to be notified when my book, You Can Just Do Things, is available for purchase.

Calling out that people who call out issues “kind of suck” is essential, thank you! It would be really easy to use an essay like this be blunt rather than intentional. And the effort required to correctly name the issue is emphasized in *Crucial Accountability*, which is aimed a bit more at managers, and reinforces your point.

This is also bad writing in movies, IMO!