I used to be a high-performing robot

Freedom is a skill you can build

Agency is having a moment. In the past couple years, it’s become a kind of catch-all buzzword — used to explain everything from startup success to personal reinvention to parenting style. Some of this discourse is genuinely useful. Some of it is insufferable. And there are real criticisms to be made.

But two of the most common ones miss the mark.

One is that agency is simply a rebrand of success — that talking about it is just another way to glorify people who are already getting ahead, a pretend explanation for why some people win and others lose that obscures the real origin in luck. The other is that agency, even if real, isn’t a concept that can be actioned, but rather a fancy label for a fixed trait like intelligence or height.

My life is a testament to the fact that neither is true. Agency is not the same as success, and it’s not innate. It’s something you can learn.

I understand why people feel otherwise. A lot of people talking about agency today are the sorts who dropped out of college to build something, or grew up in a family of prodigious mutants. They’ve always moved through the world differently. It’s easy to assume they were just built that way.

I wasn’t. When I say I learned agency, I mean it. I started with very little of it. It took me decades to change, and I only did because I had to. That’s why I care so much about this topic — and why I believe it’s possible for anyone to learn.

I have a memory, clear enough to be false, of the day in sixth grade when I decided to become a machine. I had always been unpopular, always the weirdest kid in my class — ever since my first day at a new grade school, when I showed up with a buzz cut because of a miscommunication with my parents and a barber. But when everyone was re-sorted into middle schools, there was a moment when social lines blurred and alliances were uncertain, and I made the mistake of briefly forgetting my station in life. For a few weeks I was welcomed into the popular crew, but after I admitted to having a crush on the wrong boy, the reversal was swift and absolute.

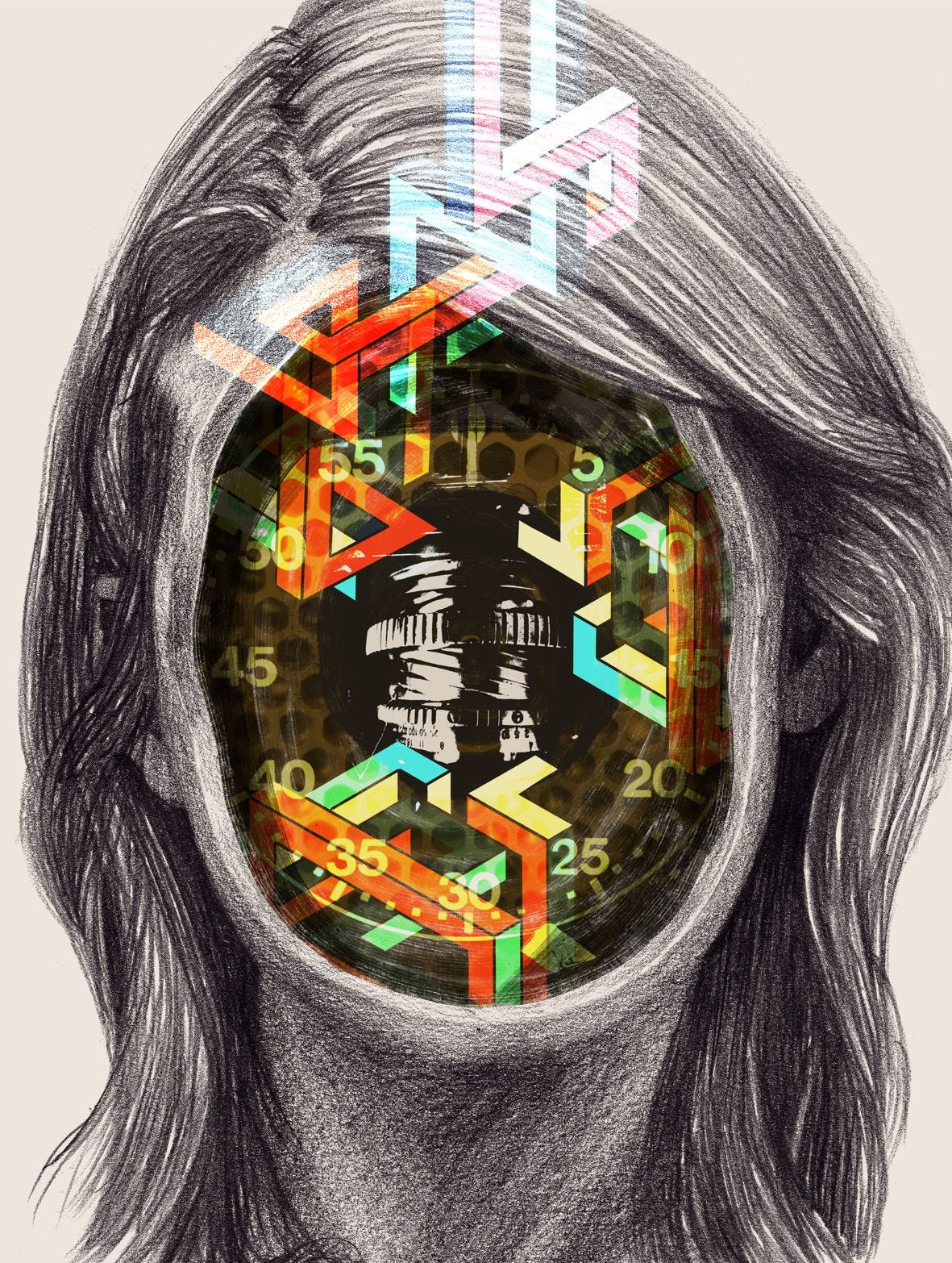

This is when I first discovered the sweet release of dissociation. I realized that I could somehow choose to feel — not none of it, exactly, but a whole lot less of it. I could just mechanically take the next step, do the next thing in front of me, and block out everything else. I would be impermeable. I leaned into it, made it a way of life. I became compulsively efficient — if I walked this way across the grounds instead of that way, I’d save 30 steps. If I pivoted 90 degrees at precisely this point, there would be no wasted motion.

As long as I was moving with intention, as quickly as possible, I didn’t have to think about anything else, including how the world responded to me. I finished the 6th grade math curriculum in months, then the 7th and 8th. No one had a plan for me after that, so I just kept repeating them for the next two years. It didn’t matter.

My orchestra teacher announced we’d have a competition, and the student who practiced the most would win a special prize at the end of the semester. I practiced 3 hours a day, determined to win. When I handed in my practice sheet, she told the class the competition was canceled. It didn’t matter.

I kept up this level of ferocious, nonspecific activity through high school and into college. I stayed in-state for school to avoid racking up debt, and was haunted by the fear that the world outside of Arizona was passing me by. I worked twice as hard, slept hardly at all, earned two degrees in four years.

Whatever ladder I found myself near, I climbed it. Departmental honors, publications, editor of the newspaper. But oddly, whenever I found myself at the top of a ladder, I didn’t feel satisfied. I’d keep going until I convinced myself I could decisively win at the thing, then lose interest and quit — because it was the thrill of achievement and nothing more serious that drove me.

This is how I ended up going to law school. I got to the end of the philosophy and biochemistry ladders and discovered I was bored by philosophizing and miserable doing lab work. Law school was there, required nothing of me but ambition, and promised a big, obvious stamp of success, so I went. I didn’t do it because I thought I’d enjoy law — I didn’t even think to ask whether I would.

I fell in love with alcohol around my senior year of college, when I discovered it was a much less effortful way of dissociating from my feelings. Finally, a way to “relax” without actually having to be there! But this meant having to drive the machine that much harder. In law school, I’d go to class during the day, study until 9 or 10, then get blackout drunk alone every night. I was brutally hungover every day, but propelled myself forward with ruthless efficiency, never letting myself slip academically. To this day, this underlies my resentment toward people who say that what drunks are missing is willpower.

As my interior life became more and more intolerable, I desperately sought stability in smaller and smaller cages. In a terrible relationship with a man who convinced me I’d never find anyone else to love me because I was too old at 25. In the jobs he told me to take. In his very expensive, drab condo where I lived but left no trace.

And I think, so help me, that I would have stayed there, had my ambition, alcoholism, and terrible relationship not collided disastrously in a series of events whereby I was forced to walk away from a big shiny prize of a job. It became clear that I needed to pick one of the three, and because I hated the other two, ambition was the easy choice.

I consider the state of addiction to be the opposite of agency. Agency is the ability to recognize all of the degrees of freedom one has. Addiction strips them away, reduces life to one option, and subordinates everything else in service of making sure that option is selected over and over again.

To some extent, you can think of addiction and agency as two sets of labels on the same dial, like hot and cold on a tap. Addiction is automaticity. Agency is its opposite. Success is a completely different dimension, consistent with anywhere the dial might be set.

When I got sober for the first time at 25, the dial turned a little bit. I was no longer so afraid of what I might do that I needed to keep myself in the smallest cage I could find. I left my boyfriend, moved into a roach-infested walkup, and felt happier and more free for the first time in memory. But inertia still kept me moving in the same direction professionally for a long time. I was still destined for a second clerkship and three years at a law firm in DC, which I droned through in a fog of boredom and depression. I found myself at the top of another ladder and realized that, yet again, I didn’t care.

It’s so strange now to look back on that time and realize that it simply didn’t occur to me that I could do something completely different. I was so locked into the narrative of a career path that even when I was miserable, the only “solutions” I considered were other jobs in the same field. I wrote to my parents that I was “the kind of bored that makes caged animals stop eating.” But I was still scanning the perimeter of the cage, looking for a slightly more comfortable corner — not for a way out.

I learned recently that people blind from birth don’t see black. They see nothing. It’s not like closing your eyes — it’s the absence of visual information altogether. That’s what my life was like then. I wasn’t weighing different options and rejecting them. I just didn’t see them.

That was right about when I ran into LSD.

For the first time, I realized there was something wrong with the fact that I didn’t care what I spent most of my waking hours doing. Before taking LSD, I knew I was sad and bored. But I’d never really felt not-sad and not-bored for any significant period of time, so on some level, it felt reasonable to expect that everything would be that way. It had never occurred to me that the quality of my experience was both critically important and significantly malleable.

Sometimes, people are warned off psychedelics because they can totally rip apart your way of life. That’s exactly what they did for me, and I’m extremely thankful. It didn’t need to be psychedelics — a couple dozen hours with a very gifted therapist could’ve helped. But I didn’t have that; I had LSD. It got me to pay attention to my experience for the first time, to turn around and look at my rationale for my career, and go, “what the fuck is this?” Once I asked this question in earnest, quitting the job was inevitable, though it was still hard, still a long time coming. Psychedelics kick-started the process, but they were only the beginning.

This is all a roundabout way of saying: Agency is really, really not the same thing as success. Agency can be helpful for achieving success, but it can be just as helpful for walking away from it. Agency is about freedom, and the ability to see what’s beyond your peripheral vision.

And it’s not something you’re born with, or that you have to develop by the time you’re 18 or you’re toast. I was 30 the first time I woke up. Not to any grand revelation. Just to the dumb, obvious fact that I didn’t want to live the life I had, and that I didn’t have to.

Sign up to be notified when my book, You Can Just Do Things, is available for purchase.

This is crazy, I've had the exact same experience. In middle school, I decided point-blank that I would be as efficient and unemotional as possible--the least amount of steps from point A to B, the least amount of words to answer a question--and shaved off unnecessary activities until I was left with nothing but work from wake to sleep. To twelve-year-old me, dissociation seemed like a revelation, a solution to all my problems, and the only explanation I could come up with for why others didn't embrace it like I did was that they were too stupid or irrational or low-willpower. I thought people who grieved their family members dying only did so because they lacked discipline; if they tried harder they too could be stoic like myself. I was sent to a series of therapists, and I remember one of them telling me, "of course, you don't want to be a robot" and I was confused--didn't everyone want to be a robot?

Same as you, this was triggered by middle-school social exclusion. I got out of it a bit earlier than you though; in third-year uni I crashed and burned, which seemed like failure at the time but in hindsight gave me a chance to rebuild my worldview relatively early in life.

Here's a question for you: Why do you think dissociation was alluring to you as a child? There are lots of sixth-graders who get excluded, but very few who turn to compulsive efficiency to cope, and (I imagine) fewer still who remain stuck like this for decades. What is it about your brain that makes it susceptible to this kind of failure mode?

I really enjoyed this post. The section about addiction hit particularly hard. It feels daft to say - but the most beneficial ideas I've learned in recovery are about doing the contrary action. Getting out of the loops of automaticity and 'going against your impulses'. So seeing the framing here of agency as on the other side of that which is automatic was nice. Even when that which is automatic was once the clear solution to a set of problems.