Many people have a delusion about commitment. It’s a delusion that’s easy to come by, easy to believe, and, if allowed to linger, capable of sinking your chances of having a satisfying life.

The delusion is that commitment is a matter of feeling something really hard — that you are committed when you have a state of emotional conviction so durable that you won’t waver in the future. You’re committed when you know in your heart that you’ll never cheat on your spouse, or abandon your book, or take money from an investor who’s not really mission-aligned.

It’s a delusion because this simply doesn’t work. Emotions are too variable. If we’re counting on maintaining an emotional state to carry us through some long-term course of action, we’re completely doomed. It’s just not possible to know whether, when you wake up tomorrow, you will be animated by the warrior spirit within, or the neurotic vacillator that hides inside of you. We all have those aspects of self, and we are all at the mercy of their random appearances. No matter how much we optimize our nutrition, sleep, psychological health, or relationships, we are still messy human beings.

So, every time you are counting on the feeling of commitment to sustain an extended effort, you’re rolling the dice. Will your bravest self happen to show up, or your weakest? If your weakest self shows up, all of the work of your previous selves might be thrown away.

An emotionally-centered view of commitment leaves you without good options: If you fail to anticipate the effects of emotional variance, you’ll be prone to adopting long-term goals, then abandoning them when your feelings fluctuate. If, on the other hand, you are wise enough to know your feelings will change, you may never dedicate yourself to anything. And, indeed, you hear people talk this way — some commitment-phobes never get into relationships because they know they will eventually experience feelings of regret and sadness. What they don’t know is that those transient feelings are the price of greater fulfillment.

The delusion is: commitment is a thing that you feel. The truth is: commitment is a thing that you make. It’s a living system of obligations and consequences that cause you to rise above your temporary frailty and work towards a goal you believe in, whether that goal takes a week or a lifetime.

A commitment system is built out of forcing functions: mechanisms that make failure harder than success. An example of a simple forcing function is hosting a dinner party so you’re committed to cleaning up your apartment. A forcing function constricts your options in a way that nudges you towards follow-through. When you set one up correctly, doing the desired thing becomes the path of least resistance.

A few other examples:

You buy an expensive outfit for a friend’s wedding, one size too small, to commit yourself to losing weight (NB: this is a terrible idea)

You book a venue for your event so you’ll have to forfeit your deposit if you back out

You invite people to a live demo of your project before your prototype is finished

I’m a huge believer in implementing forcing functions; I find it extremely powerful to make it intolerably costly for my future self to fall short of my expectations. My future self may resent me a little for doing it, but that’s an acceptable cost of doing business, as far as I’m concerned.

Imposing such a forcing function is, in fact, a vote of confidence in my future self. By contrast, if I’m not willing to implement a forcing function, it’s often a good sign that I actually don’t care that much about a given project. There are so many wonderful things I could do with infinite lifetimes — I’ve often thought it would be fun to try my hand at acting, or pick the violin back up. My willingness to commit is how I distinguish these “it would be nice” options from what I’m really serious about.

Right now, I’m writing a book, and for a long time that was an “it would be nice” hypothetical, a fantasy I considered. In reality, writing a book contains periods of playful inspiration, but it also requires structure and discipline, which are much easier to impose when I have the forcing function of a book deal keeping me accountable.

Commitment has a nearly magical way of creating the possibility of deep focus, resolve, and creativity — “necessity is the mother of invention.” In my experience, if you’re half-committed to some ambitious project, a huge amount of your cognition will be devoted to fantasies of escape, to dreaming of ways out of the discomfort: Wouldn’t it be nice if I could blow this imposing deadline? But when the path to escape is removed, the full force of your ingenuity is brought to the situation.

I could talk about many ways commitment architectures have shaped my life. But the area where this is probably most apparent is my marriage. When I met my husband, it was clear that our relationship had incredible potential. We were highly attracted to each other, and, for both of us, the other had aspirational qualities. He admired my candor and seriousness, and I loved his playfulness and emotional intelligence. We understood that we could grow together into better people.

But we also knew that it would take a lot of work. We started the relationship with severely incompatible communication styles, and very different requirements in terms of personal space. Moreover, we were both shaken from recent breakups.

Had we approached our relationship in the style of “casual dating” that’s popular these days, I don’t think we would’ve made it. Instead, we jumped in with both feet. Our first date was him moving in for a week, and our second date was me bringing him along to a professionally relevant conference abroad. We got engaged within a couple of months, and married within a year of meeting.

Today, we’re one of those annoying couples that glow with love and affection. But we had to dig really deep to get there. I can pinpoint several moments where I’m pretty sure we would’ve broken up if we hadn’t erected the barrier of marriage.

I don’t want to make the journey sound joyless. The process of adapting to each other was enriching, and it unlocked capacities in both of us that weren’t there previously. On my end, I learned to be more emotionally transparent and warm, discovering that some of my preference for solitude came from a discomfort with emotion that I grew out of. I’m now a more open, loving person, more eager to dispense affection to friends and family, and much happier this way. On his end, he learned to be more self-contained, discovering that some of his constant need for contact came from insecurity. He’s now a more self-sufficient person, who has retained his talent for connecting with people but feels less pressure to use it all the time, and he enjoys the liberty that comes from that.

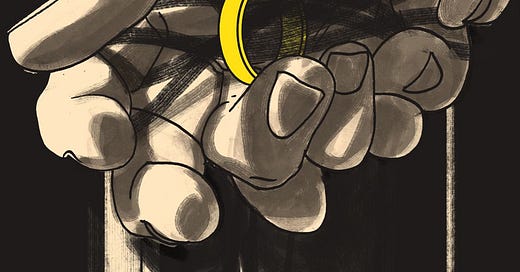

Along the way, we developed lots of little insights into our emotional patterns that were deeply helpful, not just in our marriage but in our lives as a whole. But it’s not like, at every moment, we were thinking, “oh, great, we’re growing our capacity!” At certain points in the relationship, it would be fitting to imagine us like Odysseus, who tied himself to his ship’s mast so he could hear the song of the sirens — writhing against the ropes, tempted by the prospect of breaking free, but held in place by restraints wisely tied by a previous self.

Does this sound unromantic? I can see that; there’s certainly something romantic about an easy relationship that just unfolds naturally. But I think it’s romantic that we both saw a great love on the other side of a lot of difficulty. I see beauty in the way our faith in each other allowed us to transcend our weakness and variability, that we saw something more enduring and charted a course there.

Speculation here: This could be part of why so many people seem to have trouble finding fulfilling relationships today. People wait to feel committed, rather than deciding to make a commitment. But the feeling of commitment doesn’t come easily when both people are exploring other options. If you have an easy off-ramp, you’re less likely to honestly confront your tendencies in the way that grows you into a better partner and creates real intimacy.

Anyway: I am not saying that we succeeded just because we tied ourselves to the mast. What I can say with confidence is that we increased our chances of success dramatically. I can also say with confidence that you live more fully if you force yourself to stretch beyond what you think of as your capacity.

But clearly there are limits here, right? The magic of commitment is not infinite. You probably can’t make a great marriage happen with literally anyone. Similarly, I would be pessimistic about your chances if you set up a forcing function that required you to produce a novel in a week.

This is why commitment architecture is a skill. It requires a deep understanding of just how far you can push yourself, and you can only get that through experimenting over time.

What you’re trying to do here is hurl yourself off progressively higher diving boards. You want to create a forcing function that makes it likelier that you’ll follow through on a project that’s outside of your comfort zone. Then, if it works, you up the stakes. You are looking to find yourself repeatedly in a zone of productive discomfort, where you’re pushed just beyond what you think you’re capable of. Over time, you’ll develop a sense of what your real capacity is.

Forcing functions need to have two things to work: real accountability, and real consequences.

Real accountability means that there needs to be an objective goal to hit, however meager, and someone else to witness that it definitely happened. “Make progress on the novel” does not work, because literally anything could be construed as doing this — you could tell yourself you made progress if you procrastinated, because that means you’re a little closer to being done with procrastination! “Write one sentence” would be better.

Real consequences mean that it actually has to hurt if you don’t do it. Social pressure can be a decent incentive, but it’s not always enough. Many smokers have, at some point, asked their friends to shame them for continuing to smoke, and this typically doesn’t work. The consequences have to match the level of temptation — trying to overcome a strong aversion with a weak commitment mechanism will fail 100% of the time.

One alternative is something financial: bet money that you will do it. The extreme (and especially effective) approach is an anti-charity accountability mechanism: pledging to send, say, $500 to a political candidate you despise if you fail to follow through on your commitment. Note, though, that it’s important not to make it hurt too much. If you cross some threshold of punishment, when it comes time to enforce the penalty, you simply won’t do it — which also makes for a bad commitment mechanism. Pledging to give away 1% of your net worth if you do something you really want to avoid is, for most people, a better commitment mechanism than pledging to give away 100%.

You want to begin with a commitment that gives you a real taste, but doesn’t run the risk of cementing you in a lifestyle you don’t want. Then, if your initial commitment proves satisfying, you want to escalate.

And as your commitment level grows, so too does the degree to which the goal is part of your identity, as reflected in your relationships and responsibilities. At first, you’re just doing something on your own. But eventually — especially if you deliberately set up more forcing functions — your commitments start reshaping the way others see you, and the way you see yourself.

There’s a final shift that happens if you keep going. Eventually, commitment itself stops feeling like a hack, and starts to feel like a calling, the way you can become someone worth being.

Sign up to be notified when my book, You Can Just Do Things, is available for purchase.

Thank you for writing this! I have struggled a lot to implement external commitment mechanisms in my life. I see forcing functions as setting up unfair punishment, I suspect due to some moderate authoritarian parenting and not feeling heard. Where I resist force reveals a ton about my internal programming - I hate forcing myself to not play video games (dad heavily curtailed me as a kid), but I have no problem committing to relationships (my parents modeled that through their ongoing 30-year-strong marriage). This probably sounds a bit like Internal Family Systems.

Environment and upbringing unavoidably programmed our original ideas of what we should commit to, and that continues to operate invisibly, and if we don't understand that, forcing functions are liable to make us more miserable. They make things a lot harder to see - am I pursuing this commitment because *I* want to, or because I was told it would be a good idea?

Now I'm drifting tangential to your post... When and how can I evaluate whether a commitment I've made is aligned with *me*? The odds that at any given moment I'm graced with clarity and exactness are low. Thus, perhaps commitments should be built up incrementally. If I get excited about doing idea A, and it keeps on coming up in many different emotional states, and I have some way of tracking this frequency, I can identify a good candidate for pursuing.

My problem is that I can't tell which commitments are mine, and which are from my parents, teachers, friends, books, or whatever. So it ends up that forcing functions are either unbearable (my assessment of the commitment was already wrong), or unnecessary (I landed on something that resonated immediately), and I miss out on things that require a bit more data to assess properly - where a forcing function will get me past the first 5-6 sessions of onboarding, or something similar.

So for me anyways, before applying forcing functions, I think it is prudent to have a process for evaluating potential commitments over some time, and an inventory of where I might be biased by programming. I hadn't written that out to myself until just now though :)

This is all very true. Shoutout to those whose shadows were the ones in the relationship. To make out of that and find your way out towards this is a huge achievement. Saying this mostly for myself 😮💨